Description

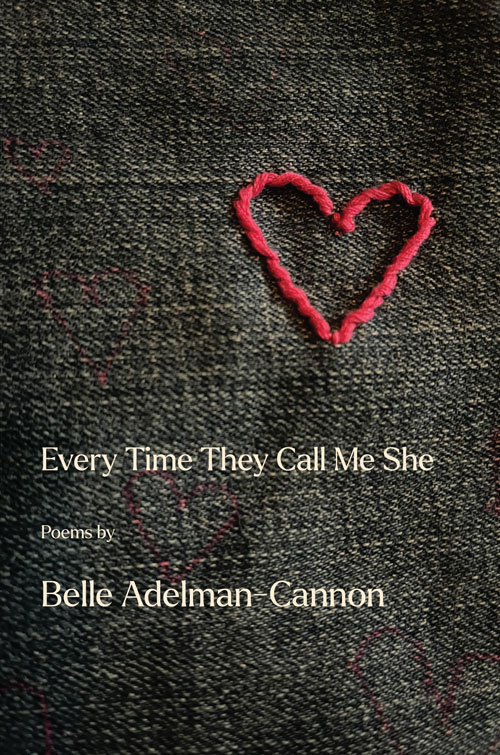

Belle Brock Adelman-Cannon

Every Time They Call Me She

ISBN 978-1-956921-26-7 (paperback)

110 pages: $19.95

April, 2024

Belle Brock Adelman-Cannon was born February 10, 2006, in New Orleans. Over the course of their seventeen years, they excelled at a variety of pursuits, including languages (French, Hebrew, German), dance, fashion design, gardening, and writing. They attended International School of Louisiana, Benjamin Franklin High School, and the pre-professional program at the New Orleans Ballet Association. They worked at Touro Synagogue, Grow Dat Youth Farm, and Henry S. Jacobs Camp. Their spiritual cornerstones were queer identity, Judaism, and their beloved hometown, especially their Faubourg Marigny neighborhood. They were exceptionally charismatic, attracting a huge number of devoted friends. These poems are their first and only publication.

They died on June 3, 2023, after which their mother discovered these poems on their phone.

“Write about your sorrows, your wishes, your passing thoughts, your belief in anything beautiful,” Rainer Maria Rilke advises in Letters to a Young Poet. With startling wisdom and imagination, the young poet Belle Adelman-Cannon explores these themes in their posthumous debut, Every Time They Call Me She. Particularly remarkable are the poems “my father” and “my bike.” Yet I most treasure the whimsy found here, whimsy that embraces the fleeting with wonder. Here the young poet offers the hummingbird an open hand “in place of a fresh bloom.” In the ars poetica, “for whom do you write?” we are told, “for the kites in the sky! / to look down on humans / and see how they fly.” What better reason? I am grateful for this collection that invites us to enter and enter again the gifted Adelman-Cannon’s world where “it’s still mid-afternoon / mid-afternoon for years / a sunny day with a starry sky cocoon.”

—Carolyn Hembree, author of For Today.

In Every Time They Call Me She, the poems of 17-year-old Belle Adelman-Cannon, readers witness the sensitive craving to understand life, while casting a net of thoughtful images that eliminate the too-common perception that today’s youth are foolishness crazed. Belle peels the weight of living daily, the expectations of shoring up, showing out, as she “strips. . muscles out like pomegranate seeds. . .looking for something,” a haunting search for meaning in life. She captures the “snot and tears (that) crawl around” her face when sick. Readers hear her a.m. angst, tired, lonely, scared, reaching for the comfort of her mother’s bed. In the cold porcelain of a daily bath, she contemplates her demise, “when the water and (she). . . become one.” In another poem amid daily angst, she “must stay present.” She prefers polaroids to selfies, “consumes beauty,” cries, carves scars to prove her identity, fights the need for sleep often. This reader and writer, who pours the sublime on these pages of verse, dictates her difference, her dread because she “was not meant for summer days. . .when her skin cries. . .humidity grabs”. .her . . “by the arms.” Belle defies expectations, breaks a contract with beauty, sees her sensitive father for whom she would “turn the clock” to her “most silly. . .age,” mature beyond her years. What a powerful testimony of a thoughtful young life today.

—Mona Lisa Saloy, former Louisiana Poet Laureate and the author of Black Creole Chronicles

These poems startle with their casual air and lack of pretension, like seeing someone beautiful suddenly naked. You want to turn around and around these statuesque poems, so finely and brutally carved. Objects tether Adelman-Cannon to earth: a bike leaning on a wall, a white shirt “laying on the floor somewhere.” But these objects merely prop up reality: “walls/ of weak papier maché/ inward they fall/ on my bike/ on my frame/ on me.” The rich, real world of Belle Adelman-Cannon is the interior world, the one thought up, unseen, amidst: “or was that yesterday/ Tuesday/ Wednesday/ or the day between.”

—Christine Kwon, author of A Ribbon the Most Perfect Blue

It’s one thing to experience life as keenly as Belle Adelman-Cannon clearly did and quite another to convey those experiences with such clarity, honesty, and devotion to writing it all down. Belle meets every experience on its own terms, whether brutally direct or subtly ironic: “suffocate me with a pillow/ we can call it art”; “I give away my happiness in exchange for forgetting it”; “the blankets weigh on me tonight/ like they’ve checked in for their shift.” I am grateful to their family for sharing Belle’s poems with all of us; I hope the admiration with which their work is received makes Belle’s memory a blessing that endures. I think of Rilke: “No feeling is final.”

—Brad Richard, author of Motion Studies

Belle Brock Adelman-Cannon’s poetry embodies the one quality that every poet shoots for, bar none: potential. In the world of poetry, potentializing one’s contemporaries and future readers to stay true to our art, is literally everything. Only by passing the torch, do our endeavors mean anything at all. I can’t wait to hold this book of poems in my hands and hunker down again into these exceedingly earnest, humble, and joyful poems. Thank you, thank you, Belle.

—Rodrigo Toscano, author of The Cut Point

It is difficult to read Belle’s book because of how reminiscent it is of my own experiences and expressions. A beautiful thing, to make people feel. That ability–that connection–separates the sacred from the profane. I see myself in Belle’s words, more acutely than I am comfortable with, and I know others do, too. Profound and intellectual but always, always inviting the reader to look in, to peer through their opened window, blending observation (of the self, society, nature) and emotional currency, often in the same sentence. Most striking, to me, is Belle’s grappling with corporeality. How does one grow up without searching the self for meaning? How does one grow up without fighting the “captors” of one’s identity? As Belle tells us, we cannot change the “rate at which the future draws near / the future draws near / it’s coming,” but we can set our deepest selves free, as Belle was learning to do: “my femininity has no captor / to her him and the others / I say run free, run free / he and they and she.” Throwing off the yoke of one’s social labels and conditioning is not easy, but Belle showed and continues to show us the importance of fighting for that freedom. And it is for Belle that we will learn to run free.

—Nikki Ummel, author of Hush

Startling, tender and honest, Belle Adelman Cannon’s poetry collection dazzles with alacrity reminding us of a life lived and realized in verve and color; both astounding in its language and haunting in its quiet revelations.

—Skye Jackson, author of A Faster Grave

Afterword

by C.W. Cannon

This is the first publication with my name on it that I’m not happy about. I would much rather these poems remained buried on Belle’s iphone while the child still lived. Fate had other plans. If Belle has to be dead, then I suppose it is a relative blessing that their mom discovered this treasure trove of Belle’s consciousness. It is deeply personal stuff. If Belle were living, they would be pissed to discover that I read what’s here, and perhaps embarrassed if I chose to share it with the world. But dead people have few options, and no time to perfect their craft and come to the exhilarating but scary determination to expose their deepest fears, struggles, and joys to friends as well as strangers. I have no doubt that given the only available choice—dead with no record of their consciousness, or dead with a public record of that consciousness—Belle would have chosen the latter. I’m not going to get into a litany of reasons I loved my child here, but I will say that Belle had the expressive and performative spark of the artist, and that, whatever they chose to do as an emancipated adult, some form of public expression was on the to-do list.

These poems are both sad and triumphant. Their concerns are germane to the life-stage of the adolescent person who wrote them. We find in them grief over the loss of childhood and productive confusion at the onset of adulthood. At their most prescient, they demonstrate a precocious apprehension of impending death, which is all the more weird since that death came much more suddenly than Belle surely would have imagined even in their most angsty moods. Belle possessed the key element identified by Romantic aesthetics as the source of poetic genius: a profound sense of the sublime, well beyond their years, coupled with an appreciation of beauty as the saving grace of an otherwise brutish and unforgiving universe. Belle was a natural intellectual, analyzing and questioning everything, wondering about the purpose of things. This quest for truth inevitably led to the knowledge of the sublime (the sense of our ultimate meaninglessness in the vastness of time and space). This fundamentally tragic apprehension was tempered by the joy Belle took in beauty, in appreciating it as well as in creating it in a variety of ways. B was always making things. The poems are the most abstract of all the things Belle made. When we lived in Dakar, Sénégal, four-year old Belle, perhaps inspired by local crafting traditions, made objects out of refuse, most commonly by lashing a couple of plastic water containers together and decorating them with tape, ribbons, or whatever was at hand. B called these creations “Woops,” and was heartbroken when we announced that the closet full of them would not be coming back with us to the States. Later on, B cut cans into interesting shapes, sometimes mimetic (generally cats and dogs) and coated them in colorful tape. As they aged, they learned to knit, crochet, and sew, and became renowned among peers as a visionary fashion designer. We honored Belle the first Mardi Gras after their death by wearing many of Belle’s fanciful designs on the streets of their beloved Marigny neighborhood (if ever a child was a Marigny child, it was Belle).

Belle took music lessons, too, but their main other artistic pursuit, besides crafting with fabrics (and plants, as a talented gardener), was dance. As the poems make clear, their commitment to dance (in the pre-professional program of the New Orleans Ballet Association) became a double-edged sword. It initiated a struggle with their developing body that sparked the fascinating interrogation of gender that is probably the most interesting objective feature of these poems. Many of the poems address a “you” that at first confused me. Was Belle addressing me (Dad), or their Mom? Or some friend? I soon came to the conclusion that the ‘you’ addressed in the poems is actually her, and, more rarely, himself. I noticed long ago that the liberation of gender, the radical freedom to choose and shape one’s own distinctive gender identity, is the unique contribution of Gen-Z to the free world’s ongoing commitment to individual self-determination. Belle was very much a part of this Gen-Z Zeitgeist, as the poems attest. Belle’s gender-fluid identity included different genders under the same consciousness. Belle was not trans, or cis, but gender-fluid. When asked in public about preferred gender pronouns, Belle said she, he, and they. The interplay between these different selves within the unitary whole is at work in many of the poems in this collection.

These poems are often the scene of acute emotional struggle. Belle used poetry as personal therapy, and also to explain things to peers that could not be said in other ways. The poems in this collection track Belle’s evolving relationship with the world within and without. What they show is not so much a child mired in depression and anxiety, but, at the end, a young adult learning to accept and master the distinct set of emotional challenges allotted to them. Few people outside Belle’s immediate family and closest friends knew of Belle’s inner turmoil, since B was always good at performing. Belle’s mom was a devoted member for many years of one of New Orleans’ many amateur dance troupes, Les ReBelles. The young Belle attended many rehearsals and was informally adopted by the group, so much so that B, too, earned a stage name, like the other ReBelles. They called Belle “Secret Agent Sparkle,” which is a good description of the infectious and joyful energy that characterized Belle’s public persona.

After the worst day of my life, June 3, 2023, when Belle died in what can only be described as a freak accident (hit by a bus), many eulogies praised the kid’s ability to brighten any room, to comfort and bring joy to people. These eulogies were not misplaced: Belle did have a zest for life, for fun, and loved nothing more than uproarious laughter with their many beloved friends. These poems don’t negate that side of B, but they show that a serious wrestling match with oneself, and a mature encounter with the facts of our mortal existence, are the best reasons to embrace beauty, love, and play wherever they can be found.

—C.W.Cannon

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.