Over the past few months we have been negotiating with the Serbian Ministry of Culture, the Crnjanski Foundation, and translator Will Firth for the rights to publish the first English translation of Miloš Crnjanski’s Roman O Londonu (A Novel of London), considered by many to be the greatest work of Serbian literature of the twentieth century, and one of the classic works on what it means to live in exile. The translation of this 800+ page epic, which will be done by master translator Will Firth, will take almost two years, so we are planning to release sometime in 2020.

The novel, which concerns a Russian emigré to London, is based on Crnjanski’s own experiences there in virtual exile in the 1940s. It paints a rather horrific view of London from the eyes from someone who lives in a constant state of rejection and alienation, beset by memories of home with no opportunity to make a home of where he is. Published in Belgrade in 1971, Roman o Londonu won Crnjanski, who died in 1977, Serbia’s most prestigious literary awards, including the Union of Serbian Writers award for LIfelong Contribution to Serbian Literature.

What we are presenting below is an essay by Will Firth which gives a brief background on the recent history, linguistic and political, of the Balkan region, and serves as a worthy prequel to the novel.

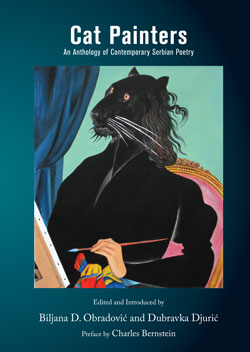

Although we only have one other Serbian work in print, it is a grand one, Cat Painters: An Anthology of Contemporary Serbian Poetry, edited by Biljana D. Obradović and Dubravka Djurić, and we are putting that on sale, today only, for half price.

Although we only have one other Serbian work in print, it is a grand one, Cat Painters: An Anthology of Contemporary Serbian Poetry, edited by Biljana D. Obradović and Dubravka Djurić, and we are putting that on sale, today only, for half price.

And look for a surprise translation from the Serbo-Croat in the very near future…

Language and Politics in Ex-Yugoslavia

Will Firth

Will Firth

(Appearing simultaneously in the bilingual Balkan anarchist magazine Antipolitika.)

For a newly formed state in a turbulent postwar situation, questions of language and linguistics are often less important than consolidating an army and administration, securing the borders, ensuring communications, producing essentials such as grain, coal, steel, electricity, and so on. This was the case when the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia was formed in 1946. Parliamentary elections had been held in November 1945, at which the communist-led National Front secured all the seats, and a government of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia was established in 1946. After reforms in 1953, Yugoslavia experimented with ideas of economic decentralization and self-management, where workers had input into the policies of their factories and shared a portion of any surplus revenue. The Party’s role in society shifted from holding a monopoly of power to being an ideological leader. As a result, the name of the Party was changed to the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. In 1963, the country itself was renamed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Language and power

These changes show that linguistic and semantic considerations were enmeshed with the political dynamics of wielding and maintaining power. The ideological language of the early Yugoslav period bore many of the traits of the discourses and diatribe in other state-socialist countries. Black-and-white, authoritarian terms such as “enemies of the people” were in common use in the immediate postwar years, when the country was ruled with the same Stalinist ruthlessness as other East Bloc states and the liquidation of real or imagined opponents was an almost daily occurrence. Following the Tito-Stalin Split of 1948 and Yugoslavia’s expulsion from the Communist Information Bureau, the country began to take an independent course in world politics, shunning the influence of both West and East. Estrangement from the Soviet Union was used to obtain US aid via the Marshall Plan, and Yugoslavia founded the Non-Aligned Movement and went on to play a leading role in it. The ideological language of the 1940s and 50s gradually began to mellow.

A noteworthy ploy in the early Yugoslav period was the codification of the Macedonian language, a long-term process that culminated in 1944 and was implemented in the years that followed. Ever since the collapse of Ottoman power in the Balkans, the historical region of Macedonia had been hotly contested territory, and its division between Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria resulted in the First Balkan War (1912-13) and Second Balkan War (1913). Bulgaria was a Nazi ally for most of the Second World War and occupied a large part of Macedonia. After the expulsion of Axis forces from the southern Balkans in 1944, the largely communist and pro-Yugoslav partisans were able to gain control. Instituting a nominally separate language in the new Socialist Republic of Macedonia, as part of Yugoslavia, was a way of cementing that power and countering Bulgarian influence. The Macedonian idiom was widely considered a Bulgarian dialect until 1944. The new Macedonian standard language for use in the media, administration, schools, etc., was based on the dialects around the cities of Prilep and Veles, some distance from the eastern part of the country whose dialects bear more resemblance to Bulgarian, and a version of the Cyrillic alphabet was adopting that is based strongly on Serbian rather than Bulgarian. The definition and drafting of a language can be seen as an important element of “nation-building” in the interests of those in power. Bulgarian and Macedonian are mutually intelligible to a high degree today, but the existence of a discrete and internationally recognized Macedonian language and nation is ultimately a product of the power dynamics of the 1940s.

Yugoslavia became increasingly integrated into the world economy, with large Western corporations producing in the country, raw materials being sold for the world market, large numbers of Yugoslav citizens working abroad (and often sending money back home), and international corporations marketing their goods in Yugoslavia—including “cultural” products such as popular music. These influences found their way into language to a greater extent than in more isolated state-socialist countries.

Many specialists consider Yugoslav policy toward minority languages to have been exemplary. Although three quarters of the population spoke Serbo-Croatian, no single language was official at the federal level. A range of community languages enjoyed official status in the constituent republics and provinces, e.g. Hungarian, Ruthenian, Slovak and Romanian in Vojvodina; Albanian, Turkish and Romany in Kosovo; Italian in Croatia, etc. A total of sixteen languages were used by newspapers, radio stations and television studios, fourteen were languages of tuition in schools, and nine at universities. As a state born out of the struggle of a multi-ethnic partisan movement, this was arguably a fair and progressive recognition of the country’s linguistic diversity. The Yugoslav People’s Army was the only institution of national significance that used Serbo-Croatian as the sole language of command.

However, this legal equality could not disguise the de facto dominance of Serbo-Croatian. As the language of almost 75% of the country’s 22 million inhabitants, and of the centre of power in Belgrade, it functioned as an unofficial lingua franca. It was a compulsory subject in all schools, whereas relatively significant smaller languages such as Slovenian, Macedonian and Albanian were not taught outside the respective region at all. Their status was correspondingly low.

On a personal note, I was stunned to see the absolute disinterest and unveiled loathing of young linguistics students at the University of Zagreb (Croatia) in 1988-89 when they were required to take a semester course in Macedonian. As if it was an imposition for them, cool cats from a northwestern metropolis, to have to learn the “primitive” idiom of some deep-south Balkan backwater.

The Serbian variant of Serbo-Croatian, with twice as many speakers as the Croatian variant, enjoyed the greatest prestige. The army used the Serbian form of the language in issuing commands.

Serbo-Croatian

Any look at language policy in Yugoslavia must deal predominantly with Serbo-Croatian. This South Slavic language was spoken as a native tongue by almost three quarters of the population—and as a second language by much of the rest.

A language with a gamut of different dialects and variants, Serbo-Croatian was effectively standardized by Croatian and Serbian writers and linguists in the mid-19th century in the Vienna Literary Agreement, which met with broad acceptance. There were slightly different Serbian and Croatian standards from the outset, although both were based on the same subdialect (Shtokavian). From 1918, Serbo-Croatian served as the official language of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

The idea of linguistic standardization often stems from the striving to create a nation and is thus a firm component of many nationalisms. Every state aspires to intervene in language and transform linguistics from a descriptive discipline into a normative doctrine that would mould language rather than recording and studying it the way it is, free and ever mutable in everyday use.

Through the subsequent fifty years of socialist Yugoslavia, Serbo-Croatian language policy amounted to a balancing act, adjusting policy and key terminology in order to maintain an equilibrium. Allowing a degree of inner diversity while maintaining the stance that it was still a uniform language served the interest of the existing system.

In 1954, major writers, linguists and literary critics, backed by the major cultural institutions Matica srpska in Serbia and Matica hrvatska in Croatia, signed the Novi Sad Agreement. Its core tenet was that “Serbs, Croats and Montenegrins share a single language with two equal variants that have developed around Zagreb (western) and Belgrade (eastern).” The agreement insisted that the Latin and Cyrillic scripts have equal status, and also that the two main pronunciation models (Ekavian and Ijekavian) be on par. It stipulated that “Serbo-Croatian” should be the name of the language in official contexts, while the names “Serbian” and “Croatian” could be retained in vernacular use. Matica hrvatska and Matica srpska were to work together on a dictionary, and a mixed committee of linguists was tasked with preparing an orthography to codify spelling. During the 1960s, both books were published simultaneously in Ijekavian Latin in Zagreb and Ekavian Cyrillic in Novi Sad. A unitarian spirit prevailed—a polycentric model of linguistic unity.

Bosnia-Herzegovina was the most ethnically diverse region of Yugoslavia and people there needed a command of both scripts. One example of how this worked in practice was provided by the main Sarajevo daily newspaper Oslobođenje (Liberation), which was published in Latin one day and Cyrillic the next.

As early as the 1950s, the communist leader and later dissident Milovan Đilas advocated a shift away from central planning toward more economic autonomy. His arguments for greater democratic input into decision-making ultimately led him to criticize the one-party state itself and rigid party discipline; he suggested the retirement of state officials whom he saw as abusing their power and blocking the road to reform. Particularly in the northwest of the country, the 1960s were marked by a gradual emancipation from the Stalinist policies followed after World War II. Major reforms in the mid 1960s introduced elements of a market economy, and a phase of democratization in the League of Communists between 1966 and 1969 saw a bigger role given to its organizations in the individual republics and provinces.

Arguably as part of this general move toward greater regional autonomy—and also rooted in a long-standing awareness of Croatian particularities—Croatian intellectuals published a “Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Literary Language” in 1967, which centrists in Belgrade perceived as a separatist affront. The Matica hrvatska challenged the Novi Sad Agreement and the common orthography and started work on its own, which was published in 1971 as the Croatian Orthography Handbook. The book was promptly banned as part of the clampdown on the “Croatian Spring” in 1971 but was published abroad in 1972.

The vying of different currents in the statist political mainstream found linguistic expression in various fields. In the 1980s, for example, there were increasing objections to the language being called Serbo-Croatian (or even Croato-Serbian), not least in Croatia. Awkward constructs emerged to take account of these sensibilities in the late Yugoslav period, e.g. dictionaries and reference works referring to “the Croatian or Serbian language” in their titles. What would a foreigner with no knowledge of the complex linguo-political situation think when a crucial definition contains the ambiguous word “or”?!

Since the end of the Cold War and the demise of Yugoslavia as a geopolitical buffer between East and West, the fragmentation of ex-Yugoslavia’s territory has been accompanied by a process of linguistic “Balkanization.” Thus the dominant discourse in Serbia and Croatia today is that they are two, albeit closely related languages. Bosnian has likewise been established as an official standard in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and in Montenegro a separate standard (including two new letters!) has been introduced and recognized by the International Organization for Standardization as a separate language. This move by the marginally dominant pro-Western camp in Montenegro is one of many tools in an ongoing geopolitical campaign to consolidate a separate Montenegrin identity and, ultimately, to check Serbian influence.

Not much has changed in a purely linguistic sense. Many of these alterations are declarative in nature, reflecting policy at a superstructural level. Despite the centripetal developments of the last two decades, the differences between the variants of Serbo-Croatian are still generally less than between the international variants of English, for instance.

To sum up with the words of the scholar Branko Franolić (1980): “Language policy in Yugoslavia consists of a series of alternations between centralist and pluralist tendencies. These tendencies are always present, only their relative emphases change. Language planning in Yugoslavia is an outgrowth from and instrument of political decision-making and overall social planning.”

The future

It is easy to criticize these developments, particularly in retrospect, and considerably harder to sketch a positive vision of linguistic policy and practice in this part of the world. Respect for diversity should be a key concern, and language must no longer be used as a tool for nationalist or power-political manipulation.

An encouraging thrust in this direction is the “Declaration on the Common Language” presented in early 2017 after preparatory regional conferences held by open-minded authors and journalists in Podgorica (Montenegro), Split (Croatia) , Belgrade (Serbia) and Sarajevo (Bosnia-Herzegovina). Its anti-nationalist theses present a counterpoint to the post-Yugoslav mania of exclusionism and the “nationalism of small differences.”

Misogynist language is another ingrained problem in the Balkans (as in many other countries). Male violence, macho culture and the depreciation of unpaid domestic work are foundations of the authoritarian and patriarchal societies we live in—and correspondingly are reflected in language. But many individuals are challenging these structures on a daily basis and trying hard to avoid modes of communication that are sexist, xenophobic, homophobic, etc. This awareness and this struggle are good preconditions for whatever “macro-linguistic” solutions and definitions are adopted in future.

—Will Firth, will.firth@t-online.de

You must be logged in to post a comment.