Abdelkader Djemaï

Abdelkader Djemaï was born in Oran (Algeria) in 1948, and has lived in various parts of France for 20 years. He has been a teacher and a journalist, as well as a regular contributor to magazines. He is mainly known for novels (the earlier ones were Camping, Gare du Nord and Un Eté de cendres), but has also written stories and drama. Djemaï has become a public figure, visible in a number of forums including YouTube. He publishes regularly on North African themes along with the culture of Algerians growing up in France, while teaching writing workshops in various venues including French prisons.

Abdelkader Djemaï was born in Oran (Algeria) in 1948, and has lived in various parts of France for 20 years. He has been a teacher and a journalist, as well as a regular contributor to magazines. He is mainly known for novels (the earlier ones were Camping, Gare du Nord and Un Eté de cendres), but has also written stories and drama. Djemaï has become a public figure, visible in a number of forums including YouTube. He publishes regularly on North African themes along with the culture of Algerians growing up in France, while teaching writing workshops in various venues including French prisons.

Foreword to Father / Son

Abdelkader Djemaï, born in 1948, has lived in France for over twenty years and become a public intellectual. His theater work, invited lectures, participation in conferences and YouTube interventions are matched by his simple mission as a teacher of writing—in prisons. He is as much an exponent of the tenor and values of modern French life as he is of North African destiny, transculturation and life in exile. The varied subjects of his many prize-winning novels make this clear, as do the two father/son crises presented in this volume—translations of Le Nez sur la vitre and Un Moment d’oubli. The former crosses between Algeria and a younger generation acculturated to France, while the latter develops protagonists of French/Italian heritage.

Djemaï does not exploit minority status. He is neither centered in a distant exoticism, a false nostalgia for Africa, nor trading on a meretricious defense of the world’s oppressed. There are examples of both these trends in recent North African writing. With Djemaï, as Abdourahman Waberi says, “We do not enter into History’s arcana, with their flood of events and revivals—but remain at the threshold of an individual consciousness.” What he has deciphered, through these individual consciousnesses, is the tone and register of universals, of the simplest depths in human experience; he has found the objective correlatives and simple twists of plot that best carry with them compassion, challenge, sadness.

On the last page of a Djemaï work the reader’s sense of a careful craft shifts to a glimpse of the whole—an awareness of formal grace. The writer is committed to the under-explored form of the novella. He is a master of suggestion and selection, allowing—in very few words—for both exact description and lyrical surge. Each of these works takes its final shape on the last page. The reader—even when not attuned as a literary critic—is suddenly impressed by two aspects of narrative form: first, that the story could end here, now, in this crushing way; second, that so much pathos has gathered and stored in so few pages to make this ending feel as it does. If the subjects were not so gritty, we would be tempted to say there is a belles-lettrist concern in Djemaï’s management of form.

One of the affective springs of this operation, in both books, is a kind of interior monologue. This is worth describing in informed terms. It is not a full-blown stream of consciousness where the flow and chop of every perception and thought is just as the protagonist would suffer it. (Blind Moment comes close to this stance, with the daring “you” of the narrative voice. This is certainly an inner voice, but the events, memories, reflections are not as realistically random as the stream of consciousness of the device’s inventor, Edouard Dujardin, or of Joyce, of James Kelman, of some of Péter Nádas’s work.) What Djemaï has developed more than most is the “indirect free style” of that other craftsman, Flaubert. What seems the stream of a tortured soul’s words gives way, at times, to narrative markers or obvious plot-movers, and, overall, to a degree of authorial presence.

Interior monologue is a perfect expression of the other psychic motor of Djemaï’s fiction: alienation. Alienation has become generalized in this author’s work. We have the impression that he has returned to this theme so often that he now sees its human commonalities, its general pervasiveness, and now pitches its pathos much deeper than many of his contemporaries. With a less dazzlingly poetic prose than Tahar Ben Jelloun’s (whom some find superficial), a less experimental form than that of Nabile Farès (who, nonetheless, is the great voice of the helpless and exiled), and protagonists rubbed more raw than those of Rachid Boudjedra (whose Les Figuiers de Barbarie, in an interior reflection encompassed by one airplane ride, is structurally similar to Nose Against The Glass) Djemaï awakens in us an intense empathy for the alienated. And he widens our focus and generalizes this alienation in a way that increases its troubling resonance. In the two novellas presented here we recapitulate Djemaï’s growth as a novelist, and we observe his sensitivity toward alienation—in one protagonist and then the other—moving from the cultural/situational to the purely situational. Djemaï is no longer a spokesman, or exemplar, of North Africans alienated by their surroundings in France. Even in Nose Against The Glass this is not the sole locus of the father’s alienation. While this kind of cultural alienation shows on almost every page, the latter narrative’s bus ride takes us ever closer to empathy with a father (it could be any father) who feels his son’s distance from him. Blind Moment, by contrast, takes place in France only, and Serrano is a member of the dominant culture. Alienation is, at first, what evolves in the father/son relationship. Later it is Serrano’s loss of his former self, of his sense of purpose. And finally, as he becomes a worn out clochard, it is his complete indifference to norms of behavior and to everyone around him. Thus we may all take different paths to a final empathy in this book—by way of tragedy, family problems, or simply the anomie of modern life.

So Djemaï extends a street person or clochard genre, like Kelman’s How Late It Was, How Late, or Tom Kaye’s It Had Been A Mild And Delicate Night, or a sort of prequel to Renoir’s film Boudu Saved From Drowning, and he does so at the peak of his powers. But beyond these and related alienations we assert once again, and strangely, that his reader’s emotions are a response to formal mastery. He has composed an empathy sonata—not too crammed with notes, with a discordant bit here and there. But fully sonata-form, resolved at the end of the last movement. And adagio, the tempo not just of loss’s courageous telling, but of gradual loss itself.

Showing the single result

-

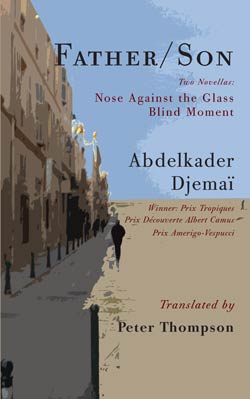

Father/Son

$16.00 Add to cartFather/Son

Abdelkader Djemaï

trans Peter Thompson

9781935084792

Winner: Prix Tropiques (1995) • Prix Amerigo-Vespucci (2002)$16.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.