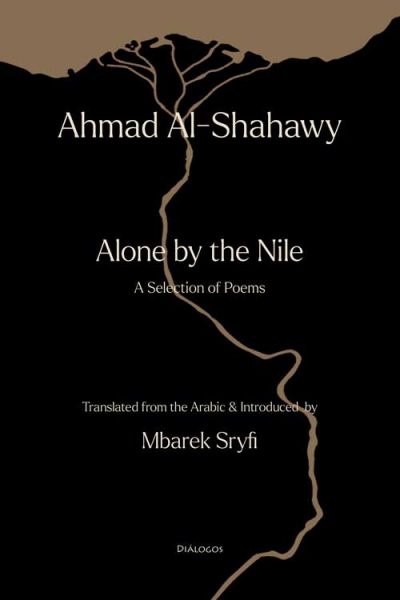

Ahmad Al-Shahawy

From the Translator’s Introduction to Alone on the Nile:

From the Translator’s Introduction to Alone on the Nile:

Ahmad Al-Shahawy (b. 1960) is that most interesting of Egyptian poets, a man full of life, audacity, passion, and mysticism. Born in a small northeastern Egyptian town, Damietta, Al-Shahawy suffered a childhood marked by tragedy. Al-Shahawy lost his mother, Nawal Eissa, when he was four years old. This sad event had a great impact on Al-Shahawy’s life and has been the motive behind his great love and appreciation for the role of women in life manifested in most of his poems and writings. Running throughout his work is a sense of longing for love and a desire to make sense of loss. Yusuf Zaydan writes that Al-Shahawy implores poetry

to bring [his mother] back. He begs the alphabet living under [his] soil for guidance. . . then emerges yet again to dig and strive to achieve three impossibilities: the first, to enter the heaven he came from; the second, to access the vocabulary of the sacred; and the third, to return to his buried poetic self.

Irrespective of its thematic obsessions, Al-Shahawy’s poetry is motivated by the desire to wander and ponder, always fueled by love, and consumed by a desire to quench his thirst for self-consciousness rooted in the simple details of every careful stroke. For Shahawy, the very act of writing itself remains a central concern.

Deceptively simple, his creative process centers on manifestations of the Muslim imaginary, with the rich, ubiquitous influence of Sufi schools of thought, and in particular through cryptic allusions. It seems no coincidence that this influence—a fraught, carefully honed dialogue with the self and the divine—is deeply rooted in mysticism.

“My poetry is my biography,” Al-Shahawy writes. He credits his success to simplicity. His poetry is concise and unpretentious, yet quite difficult to capture in prosaic paraphrase, and even more difficult to render in a different language. Both mystical and experimental, the two most recognizable characteristics of his poetry lead his poetic register to summon not only mysticism and Islam, but also a passionate cry, especially regarding the adoration of femininity, physical love, and the revival of mystic traditions.

His debt to Sufism is deeply felt, and his levitating poems are imbued with a kind of kinship. One of his most startling poems, Sleeping in Doubt, sheds light on his restless soul. Into a poem that is loaded with questions Al-Shahawy pours his ongoing emotional, psychological, intellectual, and spiritual burdens. His is a yearning that stops just short of bursting into our comfortable world and selves. Harrowing at times, its challenging simplicity is anchored in the drama and struggles of life, offering insights into the deeper meaning of the divine and sacred. What emerges are the subtleties of a fervent passion for life and love.

There is, of course, nothing inherently wrong with passion and the sacred. Even so, Al-Shahawy’s boldness was condemned by the Egyptian religious establishment, Al-Azhar, which censored his work and denounced him as a heretic.

His responses to the fleeting, elusive moments that touch everyone enable us to empathize and acknowledge tragedy. Al-Shahawy is aware of both pain and loss, emotions that, as we understand, do indeed lead the mind—unscathed, one would hope—to a divine dialogue. So intent is he on evoking deep emotions and feelings that we have the sense of living in an evanescent, borrowed time:

What if I died alone at night?

Who will enshroud my language?

Who will wipe the tears off the books keeping a vigil over my head?

Who will remind my poetry

To testify that I was without trees growing on my palms

The very frailty of ephemeral life consumes him. One enters Al-Shahawy’s poetic world writhing in agony, one that is ever so transparent and stripped of any pretensions. It is difficult not to read the collection as a testament to a tortuous search for meaning, love, and catharsis. Yet at what cost? Yusuf Zaydan concludes that “Al-Shahawy will never reach any one of his three impossible goals. He realizes it, but does not confess it. He will continue to strive to reach the impossible, and his ink/blood will spell.”

It is worth noting that there is much more here to grab you! To appreciate Al-Shahawy’s world, one must understand that it is a world shaped by pain, passion, and deep contemplation. What other role is there for poetry than to manifest a certain admiration with a skeptical expression? Sufficient unto itself, his poetry will stand as the most moving, isolated pain: a synecdoche for a poet’s life.

The present is empty

So is the future and yesterday

And I am empty

Al-Shahawy is committed to simplicity. His poetry is concise and unpretentious, yet impossible to capture in a summary.

Hassan Najmi has said that Al-Shahawy’s poetry achieves that rarest of literary goals: the stylistic essence of honesty. It also bears witness to the reality that he belongs amongst the greatest of poets. He also asserts that,

With a relentless poetic and esthetic awareness, which draws on extensive travel and research, Al-Shahawy has crafted a body of poetry stamped by beauty and a compelling, inimitable poetic voice. Passion functions as his creative essence, which rewards the reader with the portrait of a mystic soul—a soul yearning for the horizon.

How should a translator approach such a poet? Any answer involves a challenge. As we see things through Al-Shahawy’s eyes, we reach out to perceive and savor a world in the way that the poet does. His poetry bewitches, elevates, and humbles. It is an exercise in self-discovery. When I approached his work as a translator, I felt an exhilarating sense of relief that moved me deeply and reminded me of Hermann Hesse. For in reading Hesse, one comes to a painful realization: God, we are so alone!

It’s worth repeating there is much more here to grab you!

—Mbarek Sryfi (Translator of Alone on the Nile), Newtown, 2022

Showing the single result

You must be logged in to post a comment.