Bill Lavender

From “In the Thick(et) of Poetry: Meditations on 50 Years in the Language Game,” Xavier Review 37-1. (Read the entire article here.)

From “In the Thick(et) of Poetry: Meditations on 50 Years in the Language Game,” Xavier Review 37-1. (Read the entire article here.)

My mother used to read me to sleep from 101 Best Loved Poems. 101 Best Loved things—poems, hymns, prayers, etc.—were popular back in the ‘50s, sort of like the Best American Poetry of _____ books are now. Dover is still hawking a 101 Best Loved Poems, virtually the same as the one my mother read from, except it’s only in large print now. Momma also liked long narrative poems that could continue from night to night: Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha, whose meter still haunts, and—the one that made the biggest impression on me—Alfred Noyes’s “The Highwayman.” That vision of lovers who would die rather than succumb to the Law had great fascination for me, and still does. That my mother would even read it to me seemed darkly conspiratorial, as if the ethical and legal (maybe even grammatical) rules she drummed into me during the day were suspended at night. It taught me, among other things, that rules can be broken at certain hours, and that sometimes secret, unspoken realities lurk behind the content of what people say.

But it wasn’t until high school, in the late ‘60s, that I started to think of poetry as a thing I might want to do. I remember the first time I wrote something and showed it to friends. My memories of that piece are merely graphic—it was a long, skinny poem—and contextual, from my friend’s reaction. “You didn’t write that,” he said.

“Oh yeah,” I said, defiant. “Then who did?”

He had to mull this over a bit. He looked down at the sheet of notebook paper in his hand. His lips moved as if he were rehearsing things he might say. (For, though he did not know the answer, he was going to say something; he was going to have the last word.) “It was either… Franz Kafka or Frank Zappa.”

I had heard these names before, somewhere, but I hadn’t yet listened to The Mothers of Invention or read “In the Penal Colony,” and the fact that I would be accused of plagiarizing from work I did not know was infuriating. “Fuck you” was the only conceivable response.

For me, poetry (poetry as a vocation, an identity, a life’s work and obsession) did not come out of English class but out of passing notes in the back of it, handing around scraps of paper that one would get in trouble if the teacher saw.

I went to college in my hometown, Fayetteville. I hung out with the graduate poets and hippies, marched against the war, did lots of drugs, didn’t go to grad school. Instead, I moved to New Orleans, had kids, and made a living carpentering, at first, and later in the construction business. Though I stayed in touch with local poets, read and wrote during this period, in the end the exigencies of family and business took me far enough afield that I began to feel my identity as a poet slipping away.

Now, despite having devoted a long and varied lifetime thinking, reading and acting on the matter, I cannot tell you why such a thing as the poetic vocation should have such a hold on a person. I can tell you that it isn’t that feeling of gratification one gets from hearing applause or laughter at a poetry reading or getting a letter of acceptance from a magazine or a press or winning some award. These are, in the end, cheap thrills more easily (and probably more meaningfully) obtained by other means. I can only tell you that when it occurred to me that poetry was about to slip away from me, I resolved that I would do most anything to hold on to it. There followed, then, a couple of years of burning bridges after which I lifted myself out of the wreckage and went back to school.

I went back to school not because I felt I had anything to learn—though it did turn out I learned a thing or two—and not out of any real respect for the academic milieu—though I did gain an appreciation for scholarly endeavor from the experience; I did it because I couldn’t think of anything else to do. I had to do something, and school was what was at hand.

When I graduated the University of New Orleans offered me a part-time gig managing their summer writing program in Prague. I was offered this not because of my writing or academic record but because of my 20 years experience in business, for this program was foundering in its success; they had more students than they could manage. I knew how to manage things and people, and I knew how to use a budget and negotiate contracts because these are things you learn in construction.

Before that time, I had never been outside the US except for a brief foray into Canada in the ‘70s. Afterwards, I went abroad for extended periods 15 summers in a row. At first I didn’t teach. Later, they gave me adjunct faculty status. Ever the entrepreneur, I set up a low residency MFA program attached to the study abroad program. This was my introduction to university politics, that proverbial game in which everything seems so important because nothing is at stake.

They put me on the graduate faculty. I sat on and chaired dozens of thesis committees. I took over the university press. I had a big office with five GA’s, a full time study abroad coordinator, and a bunch of computers and printers. Then they fired me, and I was, after a brief flurry of petitions and irate letter-writing, relieved.

Now I’m back in construction. This time as an employee, though a well-paid one. And I run Lavender Ink and Diálogos from my house, with help from my wife, New Orleans writer and scholar Nancy Dixon, and the occasional volunteer and/or intern. And though there is always this problem or that, and though I work too hard and there’s never enough time for this thing or that (including writing), it’s pretty OK.

Links

Books

Another South: Experimental Writing in the South (ed., U of Alabama Press)

look the universe is dreaming (Potes and Poets, 2003)

While Sleeping (Chax, 2004)

I of the Storm (Trembling Pillow, 2006)

Review at Big Bridge (William Allegrezza)

Transfixion (Trembling Pillow, 2010)

Memory Wing (Black Widow, 2011)

Video of reading at River Writers

A Field Guide to Trees (Foothills, 2011)

Q (novel, Trembling Pillow, 2013)

Review at New Orleans Review (C.W. Cannon)

Goodreads #5 in Best Surrealist Literature

La Police (locofo chapbook, 2017, free download here.)

Three Letters (novel, Spuyten Duyvil)

My ID (BlazeVox, 2020)

Interviews, articles, etc.

“In the Thick(et) of Poetry: Meditations on 50 Years in the Language Game,” Xavier Review 37-1. Special issue featuring long essay and selection of poems.

An Open Letter (concerning the Lost Neruda Poems)

Long interview with poems at The Bacon Review.

Times Picayune article on UNO Press sacking.

Showing the single result

-

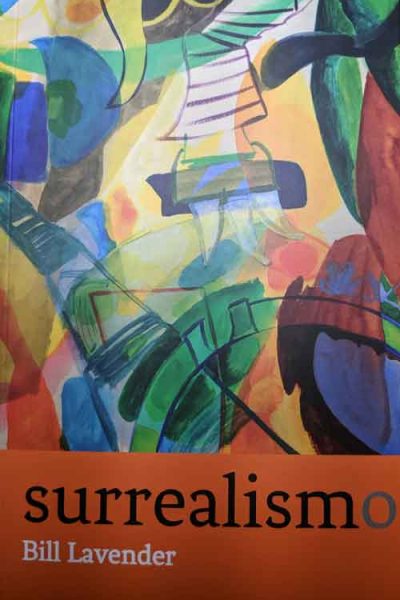

Surrealism/o

$16.00 Add to cartSurrealism/o

Bill Lavender

9781944884062

the dead try to talk and / in your case at least / succeed$16.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.