Mario Santiago Papasquiaro

Mario Santiago Papasquiaro (pen name of José Alfredo Zendejas Pineda, December 25, 1953 – 1998) was the co-founder, with Roberto Bolaño, of the Infrarrealist Movement and the basis for the character of Ulises Lima in Bolaño’s novel The Savage Detectives. Like Santiago, the Lima character is a wild adventurer and virulent opponent of the canonical Mexican tradition, symbolized especially by Octavio Paz. Santiago made enemies in the Mexican poetry community due to his vocal criticism of what he deemed inferior forms of poetry, the literary elite, and poets themselves. Gaining only slight recognition during his lifetime, he is recognized and lauded by the testimonies of his friends in the Infrarealist movement, especially Bolaño.

Mario Santiago Papasquiaro (pen name of José Alfredo Zendejas Pineda, December 25, 1953 – 1998) was the co-founder, with Roberto Bolaño, of the Infrarrealist Movement and the basis for the character of Ulises Lima in Bolaño’s novel The Savage Detectives. Like Santiago, the Lima character is a wild adventurer and virulent opponent of the canonical Mexican tradition, symbolized especially by Octavio Paz. Santiago made enemies in the Mexican poetry community due to his vocal criticism of what he deemed inferior forms of poetry, the literary elite, and poets themselves. Gaining only slight recognition during his lifetime, he is recognized and lauded by the testimonies of his friends in the Infrarealist movement, especially Bolaño.

Santiago traveled widely during his life, and when Bolaño was invited, in 2000, to give a speech on the topic of Literature and Exile at a symposium organized by the Austrian Society for Literature in Vienna, he opened it with remarks about Santiago:

…In 1978, or maybe 1979, the Mexican poet Mario Santiago spent a few days here on his way back to Israel. As he told it, one day the police arrested him and then he was expelled. In the deportation order, he was instructed not to return to Austria before 1984, a date that struck Mario as significant and funny and that today strikes me the same way. George Orwell isn’t just one of the great writers of the twentieth century; he’s also first and foremost a good man, and a brave one. So to Mario, back in the now distant year of 1978 or 1979, it seemed funny to be expelled from Austria like that, to be punished by being forbidden to set foot on Austrian soil for six years, until the date of the novel had arrived, a date that for many was the symbol of ignominy and darkness and the moral collapse of humankind. And here, leaving aside the significance of the date and the hidden messages that fate—or chance, that even fiercer beast—had sent the Mexican poet and through him sent me, we can discuss or return to the possible topic of exile or banishment: the Austrian Ministry of the Interior or the Austrian police or the Austrian security service issues a deportation order and consigns my friend Mario Santiago to limbo, to a “no man’s land” …

I imagine the scene like this: some Austrian clerk stamps Mario’s passport with an indelible seal signifying that he can’t set foot on Austrian soil until Orwell’s fateful date and then they put him on a train and ship him off, with a free ticket paid for by the Austrian state, into a temporal exile or a certain banishment of five years, at the end of which my friend, if he so desired, could request a visa and once again tread the lovely streets of Vienna. If Mario Santiago had been a devotee of the music festivals of Salzburg, he would surely have left Austria with tears in his eyes. But Mario never made it to Salzburg. He got on the train and didn’t get off until Paris, and, after living in Paris for a few months, he got on a plane to Mexico, and when the fateful or happy—depending on how you look at it—year of 1984 arrived, Mario was still living in Mexico and writing poems in Mexico that nobody wanted to publish and that may rank among the best of late-twentieth-century Mexican poetry, and he had accidents, and he traveled, and he fell in love, and he had children, and he lived a good life or a bad life, a life in any case far from the center of Mexican power, and in 1998 he was hit by a car under murky circumstances, a car that drove away while Mario lay dying alone on a street at night in one of the outlying neighborhoods of Mexico City, a city that at some point in its history was a kind of heaven and today is a kind of hell, but not just any hell—the special hell of the Marx brothers, the hell of Guy Debord, the hell of Sam Peckinpah—in other words the most singular kind of hell, and that’s where Mario died, the way poets die, unconscious and with no identification on him, which meant that when an ambulance came for his broken body no one knew who he was and the body lay in the morgue for several days, with no family to claim it, in a final stage of development or revelation, a kind of negative epiphany, I mean, like the photographic negative of an epiphany, which is also the story of our lives in Latin America. And among the many things that were left unresolved, one of them was the return to Vienna, the return to Austria, this Austria that for me, it goes without saying, isn’t the Austria of Haider but the Austria of the youth who oppose Haider and who take to the streets in protest, the Austria of Mario Santiago, Mexican poet expelled from Austria in 1978 and forbidden to return to Austria until 1984, that is to say banished from Austria to the no man’s land of the wide world, and who, anyway, could care less about Austria and Mexico and the United States and the happily defunct Soviet Union and Chile and China, among other reasons because he didn’t believe in countries and the only borders he respected were the borders of dreams, the misty borders of love and indifference, the borders of courage and fear, the golden borders of ethics.This excerpt, translated by Natasha Wimmer, appears in Between Parentheses: Essays, Articles, and Speeches (1998-2003), by Roberto Bolaño (New Directions, 2011).

From the biographical note in Poetry Comes out of My Mouth:

Mario Santiago Papasquiaro: A Brief Biographical Note

Mario Santiago (1953-1998) was a poet errant, an incessant wanderer of the storied streets of Mexico City and an adventurous pursuer of love in Europe and the Middle East.

In his mid-twenties he met a young woman, Claudia Kerik, at a poetry workshop (attended, also, by Roberto Bolaño and other infra-realists) held in a cultural center in Chapultepec Park. Mario Santiago became infatuated with her. His love was not returned. When Kerik, who was Jewish, decided to emigrate to Israel in 1977, he followed her. He went to Paris and made his way to Jerusalem and worked on a nearby kibbutz to be near her. When he finally gave up his romantic pursuit, he made a slow retreat through Europe, writing poetry whenever he could. In Vienna, he was jailed for participating in a political demonstration and was expelled from Austria. He worked as a dishwasher in Barcelona and a fisherman and crop picker in the south of France, and he was a vagabond in Paris before finally going back to Mexico.

A rebellious man with a prickly personality and anti-social tendencies, he had difficulty holding down a job. He would burn off excess energy by taking long walks, at times for days on end but always coming home to the most important person in his life, his wife Rebeca López, the familial anchor who provided him the love and support necessary to his work. He was injured when hit by a car while on one of his interminable hikes. This did not deter him from taking his long meditative walks, but thereafter he had to use a cane.

After his accident, he became reckless and would cross busy streets with no regard for oncoming traffic, and on January 10, 1998, he was struck by a hit-and-run driver and killed.

After he had been missing several days, his wife called the police. She was directed to a morgue where she identified a corpse as her husband.

Links

First Infrarealist Manifesto (English) at altarpiece

Showing the single result

-

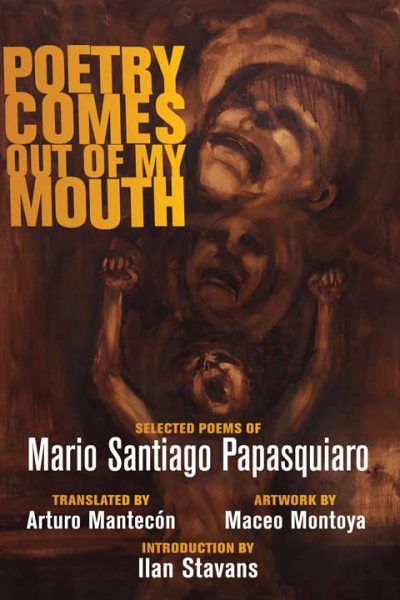

Poetry Comes out of My Mouth

$18.95 – $24.95 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pagePoetry Comes out of My Mouth

Mario Santiago Papasquiaro

trans Arturo Mantecón

artwork by Maceo Montoya

Introduction by Ilan Stavans

9781944884406

…flies in the most hallucinatory manner out of the tangled mass of Mexico’s heritage.$18.95 – $24.95

You must be logged in to post a comment.