Martín Barea Mattos

Born in Montevideo, Republic of Uruguay, on August 16, 1978, Martín Barea Mattos has published many books of poetry, including Made in China (Estuarine / Hum, 2016), Parking Barea Mattos (Una temporada en Isla negra, Chile, 2014), Conexo (with illustrations by Cecilia Mattos; National Museum of Visual Arts, MEC, 2013), Por hora por día por mes (Estuarine / Hum, 2008); Los ojos escritos (43 Premio nacional de libros y grabados, 2003); 2995/ cadáver del diecisiete (Artefato, 2002), and Fuga de ida y vuelta (La gotera, 2000). In 2007 he published the poetry CD Parking and in 2010, the DVDGrey featuring his band Por hora por día por mes, which takes its name from the book of 2008. In 2012 he put out a new album recorded live in the Montevideo Planetarium: Vino oVni (Feel de agua, 2016) and in 2016 a new album recorded in studio, Vino UFO (Feel de agua, 2016), recordings of new versions of his poems with musical accompaniment. His work has also appeared in several anthologies in both Spanish and English, including América invertida, (New México Ed., USA, 2016) and Earth, water and sky, SARAS institute; published also in the USA by Diálogos in 2016.

In 2013 and again in 2016 he organized Mundial Poético de Montevideo (World Poetry Montevideo), a festival attended by poets from 15 countries, and since 2006 he has been the regular curator of Ronda de poetas, a weekly reading series at the famous La Ronda Café in Montevideo.

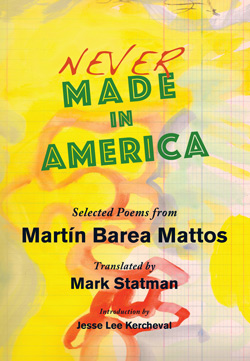

Introduction to Never Made in America: Selected Poems from Martín Barea Mattos

by Jesse Lee Kercheval

I wish I could just put a photo of Martín Barea Mattos here in lieu of this introduction. Martín as the joker in the pack of cards, as the magician, as the Master of Ceremonies at the circus of poetry, but also serious under the smile, intense, a bit dark. Or better still just embed a video of him reading, performing, his poetry here ________. I have often had the experience of hearing a poet reading his or her work and thought, That’s the voice in the poem! Now I get it! And come away with a deeper understanding of how to read the work on the page. I wish I could do that here with Martín. He embodies his work. I don’t mean that in the narrow sense that he is a talented performer—though he is a wonderful reader and a musician and visual artist, too. I mean that to see him is know where all his marvelous poetry comes from.

But I first read Martín’s work without having met him, and that was enough. The first poems I read were at a wonderful site called Las elecciones afectivas/ Las afinidades electivas that worked as a “nerve”—i.e an online magazine that featured Uruguayan poets suggested by other Uruguayan poets. I was looking for Uruguayan poets under forty for the project that became América invertida: An Anthology of Emerging Uruguayan Poets (University of New Mexico Press, 2016). There were just four poems there by Martín, but even in this brief sample his poems were witty, full of word play, a bit wicked but also with a larger vision of the world. I knew immediately I wanted to read more. I got in touch with Martín and he was immediately helpful, suggesting other poets for me to contact for the anthology. The next time I was in Uruguay, we met and I discovered his other persona, that of poetry impresario.

Uruguay is the smallest Spanish speaking country in South America, with a population of just 3.3 million people, half living in the capitol Montevideo. But it is a country full of poets. Many nights in Montevideo, there are one, two even three poetry readings in venues ranging from the national library to neighborhood bars. For the past ten years, the most regular of these has been the series that Martín runs, the Ronda de poetas, which until recently was every Thursday night, outside or inside the famous bar, La Ronda Café, on the edge of the oldest part of Montevideo, the Ciudad Vieja, a couple of blocks from the Plaza Independencia where the Tomb of General Artigas, the George Washington of Uruguay, stands, guarded by a stature of the man himself on a very large horse.

The readings start, in theory, at 10 pm, but often later, and last, more or less, until midnight. Each poet appears in turn, reads, with plenty of breaks in between for everyone to mingle and chat at tables inside or outside in the heat of a summer night or the cold wind of a winter one. The poetry in Montevideo flows through the Ronda de poetas, with readings that feature everyone from established poets down to the youngest, still students. Martin is at the heart of it all, often reading his own work, otherwise introducing, encouraging. As if that were not enough, in 2013 and again in 2016, he organized the Mundial Poetica de Montevideo, a week long festival of poetry that brought poets from the U.S., Europe and other Latin American countries together with Uruguayan poets to read every night in different locations around Montevideo.

After my first meeting with Martín, I got a copy of Martín’s book Por hora, por día, por mes, whose title is a play on the signs seen the world over in parking garages, announcing parking is available By hour, by day, by month. After reading that book, I was certain I wanted him to be in the anthology América invertida. For that anthology, I paired each Uruguayan poet with an American poet who was also a translator. I knew it would take a special translator to bring Martín’s word play and Uruguayan and world pop cultural references, his unique sensibility, into English. I was very lucky. When I appealed to Mark Statman, he, too, was intrigued by Martín’s work and willing to take on the task. This pairing went beyond ten pages in an anthology to make possible this book, Never Made in America, with poems selected from Por hora, por día, por mes and Martin Barea Mattos’s most recent collection, Made in China.

For the biographies at the end of the anthology América invertida, I asked each Uruguayan poet to list the poets who had influenced their work, Martín listed Federico García Lorca, but also Canadian poet and songwriter Leonard Cohen and Joan Brossa, the early proponent of visual poetry in Catalan. You can see that latter influence in Martín’s playful, but purposeful use of changing typefaces to differentiate between one poem or section or mood and the next. The final poet he listed was the classic American beat Jack Kerouac, a fellow restless soul. Though the amount of territory an Uruguayan can cover inside his own small country is more limited than Kerouac’s journeys, Martín’s poetry goes everywhere he cannot. I might have added that at times Martín can seem to be channeling the Uruguayan-born Isidore Ducasse, the Comte de Lautréamont (1846-1870), who was born in Montevideo and whose book Les Chants de Maldoror served as inspiration for the French surrealists. In truth, all poetry, plus all the swirling translated and untranslatable world culture that pours through internet, enters into Martin’s poetry. As a translator, Mark Statman is a perfect match for Martín Barea Mattos here, performing the difficult magic of bringing the wit, satire, spirit in the poems alive in English, letting the English language reader into Martín’s poetic universe. But be forewarned, this is a book that opens with a section called [E] Parking and the poem/admonition:

The house is not responsible for damage, fire, or theft.

Management

Jesse Lee Kercheval

Montevideo, Uruguay

Links

Showing the single result

You must be logged in to post a comment.